Just like I did for my recent rare book and beer pairing event, I wanted to share a few quick thoughts about the work I’ve been doing with incarcerated scholars in the hopes that it’s helpful for other rare books/museums folks who want to include prisons in their outreach iniatives. I have a million other thoughts about how amazing and challenging it is, but this post is just for quick outreach take-aways.

Why do this?

By now it’s no secret that my goal in life is to bring rare books (and museum artifacts in general) to people who want to learn from them but have never been given the opportunity (serving underserved populations, if you want to use field lingo). When I think about a population that is underserved in pretty much every possible way, I think of people who are incarcerated. Many current and former prisoners can’t vote, have limited access to educational resources in prison, and have trouble finding work or funding for an education once they are released. This is in addition to the fact that few prisons offer meaningful programming that discourages recidivism, even though such programs (like Common Good, or like this rehabilitation work) are effective and badly wanted by prisoners.

My classes

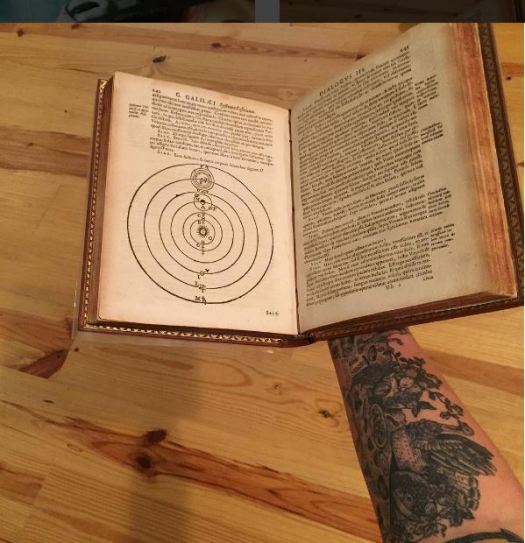

So far, I have taught two classes on subsequent weeks in one of our state prisons. Class one included a brief lecture about book history pre-Gutenberg, along with examples that the men could pass around and ask about. The majority of the time was spent discussing book history and making a list of items that the men wanted to see in the future. I learned a lot about everyone’s academic interests, and it made for a great introduction as we all got to know each other.

Class two involved a brief lecture on post-1450 book history, again with examples from our collection. In the first class, the men had been very interested in my work as an artist, so we used the discussion time in this class to talk about how we could work together on art projects and eventually an exhibit. Between this and our earlier conversation about the men’s other interests, we were able to plan how I could best teach future classes so they were as meaningful and (hopefully) fun as possible.

Our future classes are going to be structured similarly: 2-3 short workshops in a row, each about 2 hours in length. The first one is going to be a calligraphy class, where we learn about the history of different calligraphic hands and do hands on activities, and the following week come back together to see what everyone has done with what they learned. We also have other activities planned, including a book where each man makes a signature (or a gathering of pages) which are then bound together in to a single book, and a co-curated exhibit, where we all work together to build an exhibit where the men can share their work within our museum space.

A few quick thoughts

I’m lucky because I’m working with Common Good. They have been teaching in the prison for years, so know the men they’re working with and know how to navigate the bureaucracy of the prison itself. This meant a lot of the legwork of getting in to the prison to teach was done for me. If you have a program in your area that conducts classes in prison settings, get in touch with them and see about partnering (but, just like with any new program, make sure to come with a clear pitch about what you want to do and why). If you don’t have a program that exists in your community, look at models of what other folks have done, and reach out to the prison’s warden (again, with a clear pitch). Here are a handful of other thoughts about how I set up my program and what I learned so far:

- Be flexible with logistics. Prisons function in their own way, and you might run in to road blocks with scheduling, what kinds of materials you can bring in, how you can house materials, etc. Be willing to go with the flow and work with scheduling upsets and other restrictions.

- Be flexible with your class design. I had planned to spend the first half of each session lecturing on book history and then using the second half for a Q&A. This would have worked well in other classes (and in fact is a format I use pretty regularly) but the men I worked with were all so knowledgeable and eager that they wanted to deep dive into discussions well outside of what I had planned, so we did a bit less of the book history stuff and much more of an open format conversation. Because I was flexible and was willing to bend that format around when it was needed, we all got a lot more out of the class and had some solid groundwork laid for future classes.

- Learn with folks rather than teaching at them. Related to the two points above, tailor your content and have your materials ready, but don’t be overly tied to them. The prison classroom is a great example of a co-learning space, where you have a group of folks who are incredibly smart and excited to learn alongside a subject matter expert. Everyone will have a lot more fun if you teach with the goal of learning alongside your students rather than the goal of imparting knowledge to them (this applies, in my opinion, to every outreach/teaching space, but especially here).

- Handouts are very useful! I found it most helpful to put in the information I covered in my lectures, plus a bit extra for those who wanted to deep dive into a subject (NB: make sure to check the rules for everything. At the prison I went to, I was allowed to bring stapled handouts). If you want to see what I pulled together, go here and here.

- Your materials are safe! You would be amazed the number of people who I told about this project who said ‘make sure to count the books! Someone might steal them!’ I’ll keep my opinions about those comments to myself and just suffice to say that no, no one is going to steal your books.

- Let yourself have fun. This applies for me every time I teach. I have taught some of the brightest, most amazing, and most talented people I’ve ever met, and this class was no exception. Be flexible (again!), ask a lot of questions, and create space for conversation, and you’ll be amazed at what can happen.

3 Replies to “Bringing rare books to a prison classroom”